The Pro Life Argument About Too Many Babies

Science Is Giving the Pro-life Move a Heave

Advocates are tracking new developments in neonatal research and technology—and transforming i of America's most contentious debates.

Updated at 2:fifteen p.m. ET on August 25, 2021

The outset time Ashley McGuire had a babe, she and her husband had to wait 20 weeks to larn its sex. By her third, they found out at 10 weeks with a blood examination. Applied science has divers her pregnancies, she told me, from the apps that track weekly development to the ultrasounds that bear witness the growing child. "My generation has grown upwardly under an entirely different world of science and technology than the Roe generation," she said. "We're in a civilisation that is science-obsessed."

Activists similar McGuire believe it makes perfect sense to be pro-scientific discipline and pro-life. While she opposes abortion on moral grounds, she believes studies of fetal development, improved medical techniques, and other advances anchor the movement'due south arguments in scientific fact. "The pro-life message has been, for the last 40-something years, that the fetus … is a life, and it is a human life worthy of all the rights the residue of united states have," she said. "That'south been more of an abstract concept until the final decade or so." Simply, she added, "when you're seeing a baby sucking its thumb at 18 weeks, smile, clapping," it becomes "harder to foursquare the idea that that twenty-week-old, that unborn baby or fetus, is discardable."

Scientific progress is remaking the debate around abortion. When the U.S. Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, the case that led the way to legal abortion, it pegged about fetuses' chance of viable life outside the womb at 28 weeks; afterwards that point, information technology ruled, states could reasonably restrict women's access to the procedure. Now, with new medical techniques, doctors are debating whether that threshold should be closer to 22 weeks. Similar McGuire, today's prospective moms and dads tin can acquire more than about their infant earlier into a pregnancy than their parents or grandparents. And like McGuire, when they meet their fetus on an ultrasound, they may come across humanizing qualities like smiles or claps, even if about scientists see random muscle movements.

These advances fundamentally shift the moral intuition around ballgame. New engineering science makes it easier to auscultate the humanity of a growing child and imagine a fetus equally a creature with moral status. Over the last several decades, pro-life leaders have increasingly recognized this and rallied the ability of scientific evidence to promote their cause. They have built new institutions to produce, rail, and distribute scientifically crafted information on abortion. They hungrily follow new research in embryology. They celebrate progress in neonatology equally a ways to save young lives. New science is "instilling a sense of awe that we never really had before at whatever indicate in human history," McGuire said. "We didn't know any of this."

In many ways, this represents a dramatic reversal; pro-option activists have long claimed science for their own side. The Guttmacher Found, a enquiry and advocacy organization that defends abortion and reproductive rights, has exercised a near-monopoly over the data of abortion, serving as a source for supporters and opponents alike. And the pro-selection motion'southward rhetoric has matched its resource: Its proponents often describe themselves as the sole defenders of women's welfare and scientific consensus. The idea that life begins at conception "goes against legal precedent, science, and public opinion," said Ilyse Hogue, the president of the abortion-advocacy group NARAL Pro-Choice America, in a recent op-ed for CNBC. Members of the pro-life movement are "non actually anti-abortion," she wrote in another piece. "They are against [a] world where women tin can contribute as and nautical chart our own destiny in means our grandmothers never thought possible."

In their own way, both movements take made the same play: Pro-life and pro-pick activists have come to see scientific evidence as the ultimate tool in the battle over abortion rights. But in recent years, pro-life activists accept been more successful in using that tool to shift the terms of the policy debate. Advocates take introduced research on the question of fetal pain and whether abortion harms women's wellness to great effect in courtrooms and legislative chambers, even when they cite studies selectively and their findings are fiercely contested by other members of the academy.

Non everyone in the pro-life movement agrees with this strategic shift. Some believe new scientific findings might piece of work confronting them. Others warn that overreliance on scientific evidence could erode the strong moral logic at the heart of their crusade. The biggest threat of all, withal, is not the potential impairment to a item motility. When scientific research becomes subordinate to political ends, facts are weaponized. Neither side trusts the information produced by their ideological enemies; reality becomes relative.

Abortion has always stood apart from other topics of political contend in American civilisation. It has remained morally contested in a way that other social bug have not, at to the lowest degree in office considering information technology asks Americans to answer unimaginably serious questions about the nature of human life. But perhaps this ambivalence, this scrambling of traditional left-right politics, was always unsustainable. Mayhap information technology was inevitable that ballgame would go the mode of the rest of American politics, with two sides that share nothing lobbing claims of fact beyond a no-man's-land of moral debate.

* * *

When Colleen Malloy, a neonatologist and faculty fellow member at Northwestern Academy, discusses abortion with her colleagues, she says, "it's kind of similar the emperor is not wearing whatsoever clothes." Medical teams spend enormous try, fourth dimension, and money to evangelize babies safely and nurse premature infants dorsum to health. However physicians often support abortion, fifty-fifty late into fetal development.

As medical techniques have go increasingly sophisticated, Malloy says, she has felt this tension acutely: A scattering of medical centers in major cities can now perform surgeries on fetuses while they're nevertheless in the womb. Many are the same historic period as the small number of fetuses aborted in the 2nd or third trimesters of a mother's pregnancy. "The more I advanced in my field of neonatology, the more it merely became the logical option to recognize the developing fetus for what it is: a fetus, instead of some sort of sub-human form," Malloy says. "It just became so obvious that these were just developing humans."

Malloy is one of many doctors and scientists who have gotten involved in the political debate over abortion. She has testified before legislative bodies about fetal pain—the merits that fetuses tin experience physical suffering, perchance even prior to the point of viability outside the womb—and written letters to the U.South. Senate Judiciary Committee.

Her career as well shows the tight twine betwixt the science and politics of abortion. In addition to her piece of work at Northwestern, Malloy has produced work for the Charlotte Lozier Institute, a relatively new D.C. recall tank that seeks to bring "the power of science, medicine, and research to bear in life-related policymaking, media, and debates." The organization, which employs a number of doctors and scholars on its staff, shares an role with Susan B. Anthony Listing, a prominent pro-life advancement system.

"I don't call up it compromises my objectivity, or any of our associate scholars," says David Prentice, the plant's vice president and research director. Prentice spent years of his career as a professor at Indiana State University and at the Family Research Council, a conservative Christian group founded by James Dobson. "Whatever fourth dimension there'south an clan with an advocacy group, people are going to make assumptions," he says. "What we have to do is make our best effort to show that we're trying to put the objective science out here."

This want to harness "objective science" is at the heart of the pro-science bent in the pro-life movement: Science is a source of authority that'south often treated equally unimpeachable fact. "The cultural authority of science has go so totalitarian, so royal, that everybody has to accept science on their side in order to win a debate," says Mark Largent, a historian of science at Michigan Land University.

Some pro-life advocates worry nearly the potential consequences of overemphasizing the authorisation of scientific discipline in abortion debates. "The question of whether the embryo or fetus is a person … is not answerable by science," says Daniel Sulmasy, a professor of biomedical ethics at Georgetown University and onetime Franciscan friar. "Both sides tend to use scientific information when it is useful towards making a point that is based on … firmly and sincerely held philosophical and religious convictions."

For all the ways that the pro-life movement might exist seen as countering today's en vogue sexual politics, its obsession with scientific discipline is squarely of the moment. "We've become steeped in a culture in which simply the information affair, and that makes us, in some ways, philosophically illiterate," says Sulmasy, who is too a doctor. "We really don't have the tools anymore for thinking and arguing outside of something that tin can be scientifically verified."

Sometimes, scientific discoveries take worked against the pro-life motility'due south goals. Jérôme Lejeune, a French scientist and devout Cosmic, helped detect the cause of Down syndrome. He was horrified that prenatal diagnosis of the disease often led women to terminate their pregnancies, yet, and spent much of his career advocating confronting abortion. Lejeune somewhen became the founding president of the Vatican's Pontifical University for Life, established in 1994 to navigate the moral and theological questions raised by scientific advances against a "'culture of death' that threatens to have command."

When scientific prove seems to undermine pro-life positions on problems such as birth control and in vitro fertilization, pro-lifers' enthusiasm for research sometimes wanes. For instance: Some people believe emergency contraception, as well known as the morning-after pill or Plan B, is an abortifacient, meaning it may end pregnancies. Because the pill tin can prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in a woman'south uterus, advocates argue, it could stop a man life.

Sulmasy, who openly identifies as pro-life, has argued against this view of the drug—and found information technology difficult to reach his peers in the movement. "It'south been very difficult to convince folks within the pro-life community that the science seems to exist … suggesting that [Plan B] is not abortifacient," he says. "They are besides readily dismissing that piece of work as being motivated by advocacy."

And at a basic level, the argument for abortion is likewise framed in scientific terms: The procedures are "gynecological services, and they're health-care services," Cecile Richards, the president of Planned Parenthood, says. This alone is enough to make fifty-fifty gung-ho pro-life advocates wary. "Science for scientific discipline'south sake is not necessarily good," said McGuire, who serves as a senior beau at the Catholic Clan. "If anything, that's what gave us ballgame … When the moral and homo ideals are removed from it, it'south considered a medical procedure."

Even with all these internal debates and complications, many in the pro-life movement feel optimistic that scientific advances are ultimately on their side. "Science is a practice of using systematic methods to study our world, including what homo organisms are in their early states," says Farr Curlin, a physician who holds joint appointments at Duke Academy'southward schools of medicine and divinity. "I don't see any way it's not an marry to the pro-life cause."

* * *

Pro-lifers' enthusiasm for science isn't ever reciprocated by scientists—sometimes, quite the opposite. Last summer, Vincent Reid, a professor of psychology at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, published a newspaper showing that late-development fetuses adopt to await at face up-like images while they're in the womb, just similar newborn infants. As Reid told The Atlantic's Ed Yong, the study "tells us that the fetus isn't a passive processor of environmental information. It's an agile responder."

After his research was published, Reid suddenly plant himself showered with praise from American pro-life advocates. "I had a few people contacting me, congratulating me on my great work, and and then giving a kind of religious overtone to it," he told me. "They'd finish off by saying, 'Anoint you,' this sort of thing." Pro-life advocates interpreted his findings as testify that abortion is incorrect, even though Reid was studying fetuses in their third trimester, which account for only a tiny fraction of abortions, he said. "It conspicuously resonated with them because they had a preconceived notion of what that scientific discipline means."

Reid found the experience perplexing. "I'm very proud of what I did … because information technology fabricated genuine advances in our understanding of man development," he said. "Information technology's frustrating that people take something which actually has no relevance to the position of anti-ballgame or pro-ballgame and try to utilise information technology … in a style that'due south been pre-ordained." He's not going to stop doing his research on fetal development, he said. But he "will probably be a bit more heavy, perchance, in my anticipation of how it'southward going to be misused."

This fate is nearly impossible to avoid in whatever field that remotely touches on abortion or origin-of-life issues. "There [are] no people who are just sitting in a lab, working on their projects," says O. Carter Snead, a professor of law and political science at Notre Dame who served as full general counsel to President George W. Bush's Quango of Bioethics. "Everybody is politicized." This is true even of researchers like Reid, who was blindsided by the reaction to his findings. "You can't exercise this and not get sucked into somebody's orbit," says Largent, the Michigan State professor. "Everyone's going to take your work and use information technology for their ends. If you lot're going to do this, you either decide who's going to get to employ your piece of work, or it's washed to y'all."

That can have a chilling issue on scientists who work in sensitive areas related to conception or death. Abortion is "the tertiary-rail of research," says Debra Mathews, an acquaintance professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins who also has responsibility for scientific discipline programs at the university'south bioethics institute.* "If you touch information technology, your enquiry becomes associated with that argue." Although the abortion debate is important, she says, information technology tin can exist intimidating for researchers: "It tends to envelop whatever it touches."

As often as non, scientists dive into the debate, taking funding from pro-life or pro-choice organizations or openly advancing an ideological position. This, too, has consequences: It casts incertitude on the validity and integrity of any researcher in bioethics-related fields. "Anybody with money tin get a scientist to say what they desire them to say," Largent says. "That's not because scientists are whores. It'due south because the world is a actually complex identify, and there are ways that you lot can craft a scientific investigation to lend credence to one side or another."

This can have a fun-business firm-mirror consequence on the scientific contend, with scholars on both sides constantly criticizing the methodological shortcomings of their opponents and coming to reverse conclusions. For instance: Priscilla Coleman is a professor at Bowling Green State University who studies the mental-health effects of abortion. Coleman has testified earlier Congress, and pro-life advocates cite her as an important scholar working on this issue. At least some of her piece of work, however, has been challenged repeatedly by others in her field: When she published a paper on the connection between abortion and anxiety, mood, and substance-corruption disorders in 2009, for instance, a number of scholars suggested her research blueprint led her to depict simulated conclusions. She and her co-author claimed they had fabricated simply a weighting fault and published a corrigendum, or corrected update. Just ultimately, the author of the dataset Coleman used ended that her "assay does not support … assertions that abortions led to psychopathology."

"If the results are questionable or not reproducible, and so the study gets retracted. That'due south what happens in science," Coleman said in an interview. "The lesser line was that the design of the findings did not change." She expressed frustration at media reports that questioned her work. "I'm and so past trying to defend myself in these types of articles," she said. "To me, there isn't anything much worse than distorting science for an agenda, when the ultimate touch falls on these women who spend years and years suffering."

At to the lowest degree in one respect, she is correct: Many of her opponents practise accept affiliations with the pro-selection move. In this instance, one of the researchers questioning her work was associated with the Guttmacher Institute, a pro-ballgame organization. In an email, Lawrence Effectively, the co-author who serves as Guttmacher'southward vice president for enquiry, said that Coleman'south results were simply not reproducible. While Guttmacher advocates for abortion rights, the departure, Finer claimed, is that it places a priority on transparency and integrity—which, he implied, the other side does not. "Information technology'southward actually non difficult to distinguish neutral analysis from advocacy," he wrote in an email. "The way that's done is past making one's belittling methods transparent and past submitting one's analysis—'neutral' or not—to peer review. No researcher—no person, for that matter—is neutral; everyone has an opinion. What matters is whether the researcher's methods are appropriate and reproducible."

"There is a fake equivalence betwixt the scientific discipline and what [Coleman] does," added Julia Steinberg, an assistant professor at the Academy of Maryland's School of Public Wellness and Effectively'due south co-author, in an email. "It's non a debate, the way global warming is non a debate. There are people claiming global warming is not occurring, but scientists have compelling evidence that it is occurring. Similarly, there are people similar Coleman, claiming abortion harms women'south mental health, but the scientists have compelling evidence that this is not occurring."

However, fifty-fifty the academy that establishes and promotes transparent methodologies for scientific discipline research has its own institutional biases. Considering support for legal abortion rights is usually seen every bit a neutral position in the university, Sulmasy says, openly pro-life scholars may have a harder time getting their colleagues to take their work seriously. "If an article is written by somebody who … is affiliated with a pro-life group or has a known pro-life stand on it, that scientific evaluation is typically dismissed equally advocacy," he said. "Prevailing prejudices within academia and media" determine "what gets considered to be advocacy and what is considered to exist scientifically valid."

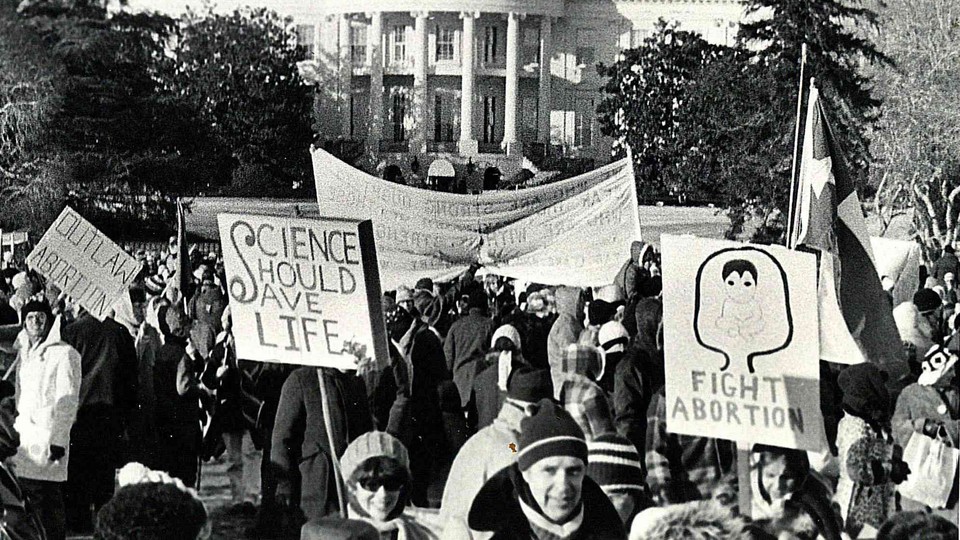

Pro-life optimists believe those biases might exist irresolute—or, at to the lowest degree, they hope they've captured the territory of scientific authorization. As the former NARAL president Kate Michelman told Newsweek in 2010, "The engineering has clearly helped to define how people think nearly a fetus as a full, breathing man … The other side has been able to employ the technology to its own finish." In recent years, this has been the biggest change in the abortion debate, says Jeanne Mancini, the president of March for Life: Pro-choice advocates have largely given on up on the argument that fetuses are "lifeless blobs of tissue."

"In that location had been, a long time agone, this mantra from our friends on the other side of this consequence that, while a picayune one is developing in its mother'south womb, it's not a baby," she says. "Information technology's really hard to make that statement when you meet and hear a heartbeat and sentry petty hands moving around."

Ultimately, this is the pro-life movement'southward reason for framing its cause in scientific terms: The all-time argument for protecting life in the womb is constitute in the mutual sense of fetal heartbeats and swelling stomachs. "The pro-life movement has always been a motion aimed at cultivating the moral imagination and so people tin understand why we should care about human beings in the womb," says Snead, the Notre Dame professor. "Scientific discipline has been used, for a long fourth dimension, equally a bridge to that moral imagination."

Now, the pro-life movement has successfully brought their scientific rallying weep to Capitol Colina. In a recent promotional video for the Charlotte Lozier Institute, Republican legislators spoke warmly nigh how data aid brand the case for limiting abortion. "When we have very difficult topics that we need to talk about, the Charlotte Lozier Institute gives brownie to the testimony and to the data that we're giving others," says Tennessee Representative Diane Black. Representative Claudia Tenney of New York agreed: "We're winning on facts, and we're winning hearts and minds on science."

This, higher up all, represents the shift in America's abortion contend: An result that has long been argued in normative claims about the nature of human life and women's autonomy has shifted toward a wobbly empirical fence. As Tenney suggested, it is a move made with an center toward winning—on policy, on public stance, and, ultimately, in courtrooms. The side effect of this strategy, however, is always deeper politicization and entrenchment. A deliberative democracy where even bones facts aren't shared isn't much of a democracy at all. It's more of an exhausting tug-of-war, where the side with the most money and the best credentials is declared the winner.

* This commodity has been updated to clarify that Mathews helps run science programs at the Johns Hopkins Berman Constitute of Bioethics, rather than the institute itself. This story also originally stated that doctors perform surgeries on genetically abnormal fetuses while they are in utero. Fetuses that are treated this mode are not necessarily genetically abnormal, notwithstanding.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/01/pro-life-pro-science/549308/

0 Response to "The Pro Life Argument About Too Many Babies"

Enregistrer un commentaire